Sadie started life as a child at risk. Exposed to alcohol and drugs before birth, she also experienced domestic violence and neglect as an infant in her Toronto home.

Taken into care and placed with a foster family at 21 months, Sadie (not her real name) was screened for developmental delays. Concerns were identified in four functional domains (areas of ability): communication, gross motor function (large body movements such as walking), personal-social skills and problem-solving. Her caseworker arranged referrals for speech-language and physical therapies—but the waiting list for access to these services in Toronto is nine months to a year. A diagnosis, if applicable, would take even more time.

Despite these delays, Sadie began receiving targeted intervention right away, at a crucial time in her neurological development. That’s not what usually happens when children go into care in Canada, but immediate developmental screening—and tailored developmental support—are part of a revolution in practice being instigated by Dr. Chaya Kulkarni, a KBHN researcher and the director of Infant Mental Health Promotion (IMHP) at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

“Between the ages of zero and three, more than one million new synaptic connections are created in the brain every second,” says Kulkarni, “That isn’t matched at any other time in our lives. Every interaction during this period has a decisive impact on brain architecture. Yet, it’s the time when we’re doing the least for kids. Frankly, it’s immoral that we haven’t been focusing more on this age group.”

Around seven years ago, Kulkarni and her team at IMHP set out to change that reality. They began with a simple question: who was monitoring the development of children under the age of five in Canada’s child-welfare systems?

The answer, it turned out, was no one. And very few were looking at their mental health, even though trauma, neglect and excessive stress have a lasting impact on the young, malleable brain. “These types of problems can lead to neurodisabilities even in children who came into the world healthy—and who could develop healthily with the right kinds of support,” Kulkarni says. “Not responding to issues at this stage sets the child up for poorer outcomes throughout their life.”

This is why a network of researchers, consultants and community-based partners are helping Infant Mental Health Promotion to develop, apply and evaluate a developmental support program called Hand in Hand. KBHN is supporting this work by funding studies of the program’s effectiveness, analyses of its socioeconomic impact and training/consultation opportunities for the people involved.

Hand in Hand doesn’t require waiting for access to a specialist; it can be administered by anyone who’s been trained for it, from an early-childhood educator to a social worker to a family home visitor.

Implemented during the child’s everyday life by parents and caregivers, and easy to deploy even in remote regions with few expert resources, Hand in Hand may hold the potential to alter the lifelong trajectories of Sadie and countless other kids across the country.

Screening and Taking Action

Hand in Hand begins with screening tools– usually the Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQs), well-validated, widely-used tools for flagging possible developmental delays in early childhood. Screening isn’t the same as diagnosis: it won’t assign a particular medical condition to the child. Rather, it will detect whether there are any signs of developmental concerns and if so, which functional domains they’re in. To flesh out their understanding of the child’s strengths and challenges, the person doing the screening will often also interview caregivers about their general impressions and observe them interacting with the child.

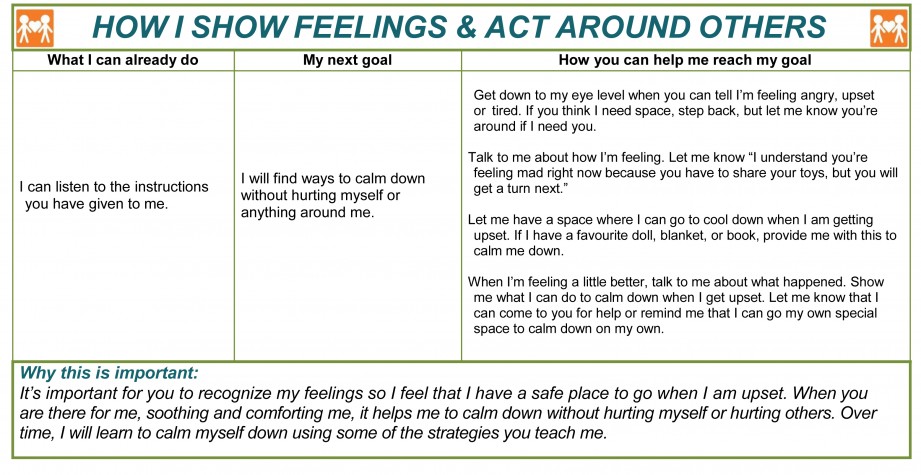

If screening pinpoints any areas of concern, appropriate referrals are still made, since Hand in Hand is meant to enhance the existing services, not replace them. The crucial next step is to create a developmental support plan (DSP). Unlike typical assessment reports, this document begins by acknowledging the strengths a child already has; for instance, it might note that they regularly make eye contact and use gestures, both examples of strong non-verbal communication skills.

The DSP then sets developmental goals and offers strategies that could help the child meet them. Ideally, the parents or caregivers assist with the selection of these goals and strategies. The goals don’t necessarily reflect typical developmental trajectories of children of the same age. Instead, they’re based on where a child’s specific strengths and challenges lie and what the next anticipated milestones might be for them. Examples of goals from the Hand in Hand manual include, “I will put names to my feelings,” “I will begin to crawl,” or “I will engage in back and forth babbling with my caregiver.”

A Hand in Hand support plan is written in the first-person voice of the child in order to encourage parents and caregivers to look at their needs from their perspective. To the same end, it always explains why a given goal is important. A caregiver might legitimately wonder, for instance, why they should put time and effort into promoting the ability to babble back and forth. “Engaging in communication where we give and take sets me up for later conversations in life,” the document might say. “I will learn that when I stop talking, you start and when you stop, it’s my turn!” Within the child-welfare context, this is a departure from more prescriptive language such as, “You must do this” or “You need to do better at that.”

If a child shows multiple delays, the family and the professional supporting them might decide to work on one thing at a time. “If I come into your house and give you a rather large document covering every single functional domain then it could easily feel overwhelming,” says Marianne Symons, the program coordinator for Calgary Health Families Collaborative, which offers family home visitation services. “The way we use Hand in Hand is by starting with one or two of the domains that show the most risk for the child. When a follow-up ASQ shows that the child is out of the monitoring zone for one skill, that’s when we would write up a new DSP for another identified risk.”

Hand in Hand’s methods for pursuing goals are based on pre-existing evidence and are reviewed by a panel of experts each year to ensure they’re in line with the most up-to-date understanding of early childhood development. “Honestly, we didn’t come up with anything earth-shatteringly new in terms of strategies,” Kulkarni says. “What we did was put them into a format that’s accessible and that makes sense to people.”

The strategies are also intended to fit easily into the child’s daily routine. The Hand in Hand manual contains a variety of options for furthering each goal, so that the person preparing the DSP can tailor it to a specific family. For instance, a mother who lives in a remote area and who doesn’t own a car might not be able to get to the library twice a week. Maybe it would be more realistic for her to write short, simple letters to her child and practice reading them together. “We want to build on the family’s strengths instead of making them feel like, ‘Geez, I can’t do enough for my kid,’” Kulkarni says.

Each and every strategy in the Hand in Hand manual is designed to help strengthen the connection between the child and their primary caregivers. Research has shown that these relationships are crucial for the health and progress of all young children. “If a child needs to learn to walk, the Hand in Hand strategies won’t involve instructing them to practice it by themselves,” Symons says. “Instead, they’ll be along the lines of, ‘Encourage me to begin walking by offering me physical support, like holding my arms or standing near me to make sure you can catch me if I fall.’ Strategies are always interactive, and that’s a big part of why the process works.”

A relational strategy can be contrasted with a behavioural one, where promoting or discouraging particular types of conduct is the main focus. “Sticker charts, time-outs, sitting on a chair when you’ve misbehaved and so on—that’s not what children benefit from the most when they’re very young,” says Brenda Packard, a child-welfare supervisor at the Children’s Aid Society of Toronto, a KBHN trainee and one of Hand in Hand’s developers. “We want caregivers to focus instead on growing their understanding and empathy for the child’s needs.”

Once it’s complete, the DSP is shared with everyone who regularly cares for or supports the child, whether they be parents, grandparents, foster parents, adoptive parents, babysitters, educators, social workers or access workers. This helps to keep them all working toward common goals. After a few months, the child will be rescreened to see what the next DSP will address.

For Sadie, attention from a foster parent and a children’s services worker who were both well-versed in Hand in Hand reaped results. Eight months after her first DSP was written, she was meeting new developmental milestones in all domains. What’s more, her biological father, struck by the changes he saw in her, decided to engage with her DSP and, after a while, demonstrably started grasping and paying attention to her needs. “Sadie got to leave care, and she now lives with her dad,” says Packard. “He still follows the plan and realizes that she won’t automatically develop by herself—that she relies on their relationship.”

The Early Intervention Gap

One of KBHN’s main areas of focus is enabling early detection of developmental delays and neurodisabilities. The sooner an issue is identified, the sooner it can be treated and the better the chances of optimal outcomes—in theory. In practice, supports and services can be scarce, particularly for babies, toddlers and preschoolers. In places where relevant supports and services exist at all, one can easily wait up to a year to access them—even longer for those that require a diagnosis. “Furthermore, if kids’ issues are due to, say, early-life trauma, we don’t have a formal diagnosis for that,” says Dr. James Reynolds, KBHN’s interim chief scientific officer. “They still need and deserve interventions.”

A DSP can be drawn up immediately after screening, allowing for some form of intervention to begin right away. The pay-off of doing as much as possible as soon as possible is hard to overstate, according to Packard. “We’re still fighting a lack of awareness around how important the earliest years are, how much development actually happens and how much easier it is to intervene at that time,” she says. “What we often see is kids who are five or six years old coming into care because they’re so out of control that no one can manage them. There’s no self-regulation, and often there are all kinds of other delays as well, and we’re thinking, ‘Oh darn; we wasted all that precious time.’”

Hand in Hand can be used outside of the child-protection context as well—in childcare settings, for example, or in the homes of any and all families with young children who happen to be facing developmental challenges. On average, kids who are in contact with the child-welfare system run a heightened risk of delays, but plenty of others are falling through the cracks, too. The best available data about the general population of Canadian children comes from the Early Development Instrument (EDI), a questionnaire completed by kindergarten teachers across the country about their students, who are generally four or five years old at the time.

Currently, approximately 27% of the children covered by the EDI are found to be vulnerable in at least one developmental domain.

“We have virtually no data about kids under that age, though,” says Kulkarni. As it begins getting collected via Hand in Hand and other programs, she adds, it will be important to share it with policy makers. “I think governments have avoided this question so far because it could prove to be a Pandora’s box. Once we open it up, who knows what we’ll find inside. Are we going to be able to meet the needs of all the kids we identify? Initially, probably not. But if we don’t actually start getting understanding of the depth of the challenge, we never will.”

Nurturing the Seed

As Hand in Hand started getting used in the early 2010s, Kulkarni and her colleagues at Infant Mental Health Promotion realized they needed a version that was better suited for supporting Indigenous families, especially since many of the workers doing so were not Indigenous themselves and stood to gain from extra guidance. The eventual result, a program called Nurturing the Seed, was developed with the expertise and input of elders, advisors and other Indigenous partners from across Canada. “We’ve done our best to be respectful of Indigenous people by getting their feedback toward a meaningful resource that honours Truth and Reconciliation and OCAP principles,” says Donna Hill, an administrator for Infant Mental Health Promotion, project lead for Nurturing the Seed and a member of the Upper Mohawk from Six Nations of the Grand River.

Hand in Hand and Nurturing the Seed share the same purpose and general approach, according to Hill. One of the primary differences between them, she says, is that the latter incorporates more of the worldviews, values, rituals and parenting practices distinct to Indigenous communities in Canada. For example, in most Indigenous languages, there isn’t a word that perfectly matches the Western notion of “development.” Rather than necessarily expecting kids to reach particular milestones by a precise age, there tends to be a stronger focus on “supporting the distinct abilities of each child, encouraging each one to follow a unique path grounded in their strengths,” as the resource’s manual puts it. To create a more flexible framework, Nurturing the Seed might suggest which strategies and activities could be appropriate for a “baby” or a “toddler” rather than, say, a child of 12 months.

The project offers an opportunity to honour and mobilize Indigenous knowledge related to child well-being, along with culturally specific strategies for promoting it. For instance, drumming is suggested as a means of learning about turn-taking, practicing playing cooperatively with other children, strengthening motor skills and/or gaining a sense of spiritual identity. “Drumming might not be something that all Indigenous people do,” says Hill, “but it’s an example of how traditional practices can be reintegrated into parenting in a way that contributes to the child’s development, in both the Western sense and the traditional sense.”

Not every Indigenous family is practicing traditional ways or is interested in doing so. With this in mind, the program “primarily aims to make sure workers are building a relationship with the family,” Hill explains, “so that they understand their unique needs and respect their beliefs while also providing them with support for their child through the developmental planning process. The idea is to explore the suggested options with the family and see what’s meaningful to them in particular. It’s the same with Hand in Hand, actually, but Nurturing the Seed emphasizes even more that you’ll be following the family’s lead.”

Encouraging front-line service workers to become a careful student of each individual family is part of Nurturing the Seed’s trauma-informed approach. From the residential-school system, which aimed to undermine Indigenous cultures by eliminating parental involvement in kids’ upbringing, to the “Sixties Scoop,” a time when the proportion of Indigenous kids in the child-welfare system skyrocketed, Canada carries a long legacy of separating Indigenous children from their families and communities. “The impact was and remains devastating,” says Nurturing the Seed’s manual, “with severed ties between Indigenous peoples and their languages, cultural practices like traditional child rearing practices and ceremonies, medicinal practices—and so much more.” Workers who recognize this inter-generational trauma are better prepared to support and engage Indigenous families.

To this day, the number of Indigenous children in care is highly disproportionate. Métis, Inuit and First Nations organizations are currently working with the federal government to draft legislation that will result, it is hoped, in greater Indigenous control over child welfare services, the apprehension of fewer children and a shift of emphasis toward other measures for promoting child well-being, such as alleviating poverty and providing opportunities for parents to enhance their skills.

There’s a big push to develop the Indigenous workforce in this area, as well as to recognize and further equip the resources that already exist—including informal ones such as neighbours, extended family and so on. Because it uses a “two-eyed seeing” approach (in other words, it tries to bring together the strengths of both Western and Indigenous perspectives), Nurturing the Seed can help Indigenous professionals and community members to “bridge gaps or disconnects between their lived experiences, their exposures to Indigenous approaches and/or their formal Western-oriented education and training,” according to its manual.

Against this backdrop, five Indigenous communities from across Canada have agreed to be part of a pilot project, funded in part by KBHN, that seeks to evaluate how Nurturing the Seed could help with particular objectives that they will be identifying. This project will see the program applied beyond the foster-care system. One of the organizations that will be training staff in the resource is the Temiskaming Native Women’s Support Group, which helps to deliver a variety of services including childcare and child/parent play programs in the Temiskaming district of Ontario. “It will be good to hear from these communities and see how they want to use Nurturing the Seed and how they receive it,” says Hill. “We’re forming a research advisory group for our Indigenous work as well. All to say: we’ll be continuing to consult and learn as we roll out Nurturing the Seed.”

Assessing Impact

Pat May, an Ajax, Ont.-based foster parent, has provided a home for babies and young children for the past 32 years. When she was introduced to developmental screening tools a few years back, she appreciated them immediately. “We have a variety of children coming through our home, each with their own needs,” she says, “and as much as we try to be vigilant, it’s easy to miss some of their challenges.”

When it came to DSPs, May was initially a bit skeptical of some of the proposed strategies. “There were some really simple things there, like playing peek-a-boo. I thought, ‘Really? An activity this basic is going to make a difference for this issue?’ But I utilized them on a regular basis and when it started to work, I was like, ‘What do you know? This is great!’ I would encourage parents to be open to trying the strategies. There’s plenty to gain and nothing to lose.”

Like May, many of the parents supported by Marianne Symons’s home visitation team in Calgary have seen tangible progress after trying strategies from Hand in Hand. “It’s affirming and hopeful for them,” she says. “It encourages families to be more open and engaged in the development of future DSPs, to stay involved with the home visitor and to continue developing their parenting skills.”

Hand in Hand can build capacity not only among caregivers but also among front-line workers who are in contact with kids in care and other at-risk children. “For me, that’s been a really exciting part, to bring this training to the workers at my agency,” says Brenda Packard from the Children’s Aid Society of Toronto, explaining that it’s familiarized them with the concept of infant mental health and allowed them to provide a different kind of support than before. For example, a baby’s failure to gain weight might be viewed not simply as a physical problem but as part of a larger picture that could potentially involve emotional trauma, neurodevelopmental issues or an underdeveloped relationship with the primary caregiver.

Even Marianne Symons’s workers, who already had a strong background in early childhood development, claim that Hand in Hand has made their job easier. “Before, we were talking to parents in more general terms, whereas now we’re able to give them a focused, intentional, written strategy. My home visitors feel they’re able to be much more clear with parents about precisely what they could do to make a difference.”

According to Symons, home visitors within Calgary Health Families Collaborative have written DSPs for a total of 265 children who showed a lag in an initial ASQ and who went on to get a follow-up test later on. Among these children, 240 showed measurable improvement while 25 did not. Given that there’s been no control group, it’s hard to say how many of the kids would have made progress without the intervention. Still, Symons says, it’s an encouraging rate.

As promising as the anecdotal evidence for Hand in Hand’s effectiveness is, it will take scientific evidence to drive its adoption on a nationwide scale. To that end, a KBHN-supported randomized controlled trial is underway in Toronto, led by Packard and supervised by James Reynolds, the network’s interim chief scientific officer. It is designed to measure Hand in Hand’s impact for the specific sub-population of children that has accessed it the most so far—those who are in protective care or who are in contact with child-welfare services.

Participating children who show possible delays are randomly assigned to receive either a DSP (along with any other relevant services) or the current standard of care alone (supplemented by a DSP once the study is complete). The results comparing outcomes for the two groups are expected in the spring of 2019.

“KBHN’s role here is to help build the evidence base for the theory that not only is identifying developmental delay during early childhood possible, but that it is worthwhile because we can do something about it,” says Reynolds. “Providing that evidence will be the first step in changing the standard of care for this population, such that screening and intervention become the accepted standard.”

Should the trial reveal that Hand in Hand doesn’t work as well as hoped, it will point to ways of improving the intervention. “We may, for instance, find that some domains of function respond more to it than others,” Reynolds says. “Knowing this would allow us to go back, modify the parts that don’t seem to be having the desired impact and then reassess the tool.”

With additional studies and a bigger overall data set, it will eventually become possible to figure out which children stand to benefit from Hand in Hand the most. “We’ll want to replicate this type of study in different contexts, in various parts of Canada where the systems of support might not be the same as in Toronto, to see if the effects are robust and if they occur across different populations,” Reynolds says. “The program needs to be iterative and built upon what we obtain from constant evaluation and re-evaluation.”

The Power of a Network

Should Hand in Hand prove effective at putting kids on healthier trajectories, not only they themselves but also Canada as a whole could benefit from its wide-scale uptake. KBHN’s health-economics group is currently modeling the long-term socioeconomic gains we might expect to see in education, justice, healthcare, social services and other publicly funded domains. “The potential return on investment includes lowering the risk of adverse mental-health outcomes, increasing school readiness, reducing the need for special-education services, and improving overall educational success rates, which we know translates into better long-term health outcomes,” Reynolds says.

In the meantime, Hand in Hand is steadily gaining ground. An increasing number of trainers are now able to show front-line workers how to use it. It is making inroads into remote regions such as Slave Lake and Northern Saskatchewan. It was recently translated into French. The province of Alberta is adopting it as standard protocol for all children involved with child-protection services. And KBHN is helping to keep the various partners connected and working together toward maximizing impact. “It’s a different way of looking at research outcomes,” says Reynolds. “One of the things that excites us about this project is that front-line service workers who connect with families on a daily basis are our research team. They’re the ones who are collecting the data, assessing the kids, supporting the intervention and bringing the findings back to analyze. By engaging them with research projects, we’re building their capacity.”

“There’s also an impact at the organizational level,” he continues. “For instance, we see the opportunity for new knowledge and protocols to become embedded in the administrative structures of child-welfare agencies, which in turn could stimulate discussion at the public-policy level. What all of this means is that we’re looking at ways to help individual kids, yes, but also to scale up this type of programming to the whole of Canada. Building the partnerships we need to get there is the unique role KBHN can fill.”

Stories by Samantha Rideout