An AI-Powered Solution for Sound-Sensitive Kids

August 14, 2024 | News

The majority of kids with autism find certain sounds painfully distressing. They’re often forced to choose between comfort and full participation, but a new technological solution is poised to change that.

When Michelle Auton’s son Connor was around 12 years old, a routine trip to the grocery store became a memorably difficult moment. “There was a loud, piercing beeping noise, and he couldn’t cope,” recalls the British Columbia-based behaviour analyst. “He was so upset that he couldn’t recognize we were telling him we could leave.” In the end, he found relief when his parents carried him out of the shop, leaving the groceries behind.

Connor, now an adult, has autism. He uses a tablet with a touch-chat app to communicate, and Michelle helps to advocate for him as well. Like an estimated 50 to 70 per cent of people on the spectrum, he’s hypersensitive to certain sounds. This phenomenon, known as decreased sound tolerance or sound sensitivity, can be very distressing and debilitating.

Some people describe it as a sensation akin to physical pain, according to Dr. Michelle Schmidt, the executive director of Autism Community Training, a nonprofit in Burnaby, BC. “And the way that people respond to the stimuli is going to differ,” she explains. “But in kids, it often manifests in covering the ears, crying out, engaging in ‘stimming’ or even eloping from a particular environment.”

Coping strategies exist. When Connor was in elementary school, his teachers let him exit the room whenever he experienced sensory overwhelm. Some children carry earplugs or headphones to mute the soundscape as needed. But these tactics prevent kids from hearing important sounds such as the teacher’s voice, and they interfere with their full participation in activities. “Being able to leave the classroom isn’t the ideal solution when your friends and your potential learnings are in it,” emphasizes Michelle Auton.

A Kids Brain Health Network-funded team based at Simon Fraser University is addressing this barrier by developing a wearable, artificial intelligence-powered app that can mask or filter out whichever specific noises the user finds aversive, while leaving the rest of the soundscape intact. Ultimately, this technology aims to empower people with decreased sound tolerance and their families to live their lives freely and comfortably.

“I would be thrilled to see families using the app to improve their access to recreational activities that they normally wouldn’t partake in, like going to the movies, a hockey game or the mall,” says Dr. Elina Birmingham, one of the project’s two principal investigators. “And I want to see kids using it to be included in a regular classroom. Those are the kind of goalposts we and our partners have in mind.”

The Impact of Decreased Sound Tolerance

Kenzie Curby, an inclusive-education support worker, autism consultant and autistic self-advocate, has firsthand experience with decreased sound tolerance. “It’s impacted me ever since I can remember,” she says. This background helps her to understand the needs of the student she supports, who uses headphones to get through each day.

She says her work is challenging — and not because of her duties on the job. “The hard part is everything else: the bells ringing and people chattering.”

Not everyone appreciates how challenging sound-tolerance difficulties can be, she says. “A lot of people think we should just cope with it and move forward. But if they had a broken ankle then nobody would expect them to run a marathon. The same thing goes for those of us that need sound accommodations through the day: we can’t ‘run’ without them.”

In some cases, kids with decreased sound tolerance get excluded from school entirely, according to Michelle Schmidt. “People think, ‘There’s something in the environment that’s upsetting to them, so let’s remove them from the environment,’” she says. “And obviously, that’s extremely problematic.”

(From left to right) Dr. Elina Birmingham, KBHN trainee Dr. Behnaz Bahmei and Dr. Siamak Arzanpour in their lab at Simon Fraser University

When children do attend school, the condition can prevent them from socializing and learning effectively there, says Dr. Siamak Arzanpour, a scientist working on the KBHN-supported app. “And so, it can seriously affect how kids develop,” he adds.

Not only the child with sound sensitivity themselves but also their family can be impacted. When Michelle Auton was raising her children, leaving the house was an elaborate endeavour. “Our life was like a football game: we were living out of a playbook,” she says. “If we were going somewhere, we needed to have a backup plan. If our child can’t cope with the sounds at Christmastime, what are we going to do? Can we go to this relative’s house? Do they have a space where it’s quiet? Who will leave with him and who will stay with the other kids?”

“Overall, it’s life-altering,” she concludes.

From Concept to Prototype

Even though they both work at Simon Fraser University, Elina Birmingham and Siamak Arzanpour are unlikely research partners. Their fields of expertise haven’t traditionally overlapped, and they may never have met if they hadn’t once been seated together at a dinner party. Birmingham conducts autism research in the Department of Education while Arzanpour is an associate professor in the School of Mechatronic Systems Engineering.

“We felt that combining our skill sets in an interdisciplinary approach could be really helpful for finding a solution that’s better than what kids are currently using for decreased sound tolerance,” says Birmingham.

Children with sound sensitivity have tested the app in a virtual-reality environment

KBHN has been involved with the project from the beginning. In addition to funds, it has also made contributions such as introducing the researchers to organizations that have access to people with autism and their families. Along the way, these partners with lived experience have defined the functionalities they would like to see in the app and provided constructive feedback on concepts and iterations.

The app uses two main AI algorithms: one that detects aversive sounds and one that separates them from the rest of the sonic environment, so that a tolerable version of it can be sent into headphones worn by the user. This software is currently hosted on a phone.

Not everyone with decreased sound tolerance finds the same noises distressing. So the detection algorithm must be able to learn to recognize an individualized set of aversive sounds.

“The way that AI works is similar to how we learn things from childhood,” explains Arzanpour. “You need to train the brain of the system with inputs.” By way of demonstration, the research team has trained their system for several commonplace triggers including dogs barking, sirens, babies crying and construction.

When it comes to dealing with these noises, there are different options available to users. “The app could activate noise cancelling, or filter out that sound and let everything else through,” explains Birmingham. “For example, if I’m talking with you and there’s a dog barking, then we could still continue the conversation, but the barking is gone.”

It can also mask the sound with a different one. “A lot of kids seem to like calming nature sounds,” says Birmingham. “They can choose from several masking-sound options on the app, or choose to filter out the problematic sound. Once they’ve programmed their preferred settings, the sound detection and management processes are automatic.”

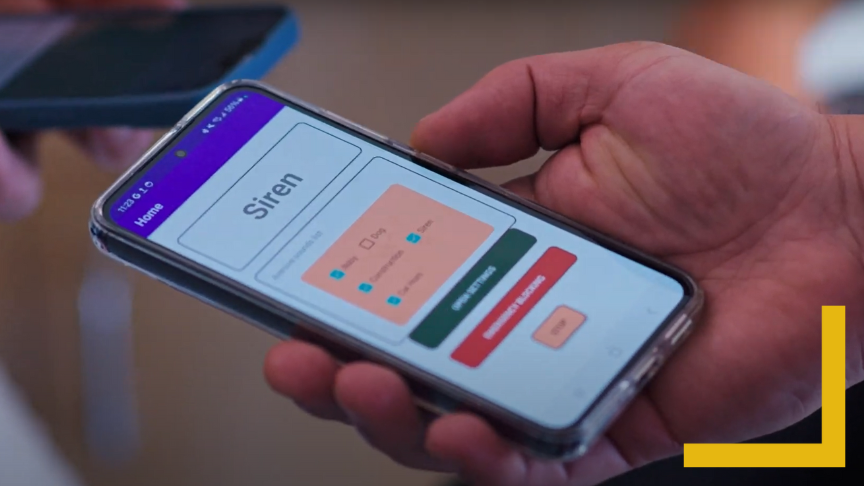

The prototype’s user-friendly interface can be toggled on a smartphone

For users’ safety and awareness of their surroundings, the app can communicate about certain important sounds. “We can have an alert sent to let users know that there’s something in their environment that they need to pay attention to, like a siren,” Birmingham says. “Or we can change the way that siren sounds. So it’s still coming to their ears, but it’s something more tolerable to them.”

As of 2024, the team has an app prototype that autistic individuals, including Kenzie Curby, have tested in a virtual-reality environment.

“One of the options was to mask the siren noises with the sound of rain,” Curby says. “That’s a sound that I remember being very calming ever since I was a toddler. I was looking forward to the moment it would turn on, because of the sense of safety it gives me.”

Michelle Auton is also excited by the prototype and how easily it could fit into everyday life, without drawing stigmatizing attention. “This is a small tool you can put in the palm of your hand: you can have it on your phone and in your ears,” she says. “Nobody looks at you funny anymore because you’re wearing earphones.”

“All of us rely on technology,” she continues. “For instance, some of us don’t know the phone numbers of the people we love because technology remembers things for us. As a mom and a behaviourist, I’m seeing tech finally coming into the lives of people with developmental disabilities in a way like it never has before.”

A Promising Path Forward

The team is now field-testing the app in a small pilot study. If that goes well, they’ll conduct more robust clinical-validation studies.

“We’re also be developing a business plan for getting the app into the hands of the people that need it,” Birmingham says. KBHN has been assisting on the commercialization front by providing business training and coaching to the investigators, their students and their postdocs.

Kenzie Curby looks forward to the time when the app will be available nationwide. “One of my strengths is a strong sense of justice,” she says. “I’m an advocate for myself, but I also want the world to be understanding of every autistic individual. Making sure that all people are looked out for is really big for me. And for a lot of people, this solution is going to be a game-changer.”